By Mary Grace Nguyen

I Due Foscari is one of those opera

that isn’t performed often enough. Having seen it at the live relay in the

cinema [27th October 2014], nicely hosted by Stephen Fry, I managed

to learn more about Verdi’s earlier opera and unexpectedly enjoy it at the same

time. I disregarding what online reviews had said about the production.

It

was performed twenty years ago in Covent Garden and in 2012 the Los

Angeles Opera presented a newer production with Plácido

Domingo,

the company's general

director, to

sing the role of the baritone Doge of I Due Foscari. Yet, we know Domingo as a world

leading tenor from as far back as his opera career begun. In the 60s, he

auditioned for a baritone role in Mexico National Opera but was requested to read arias and lines in a

tenor range, which stayed with him ever since. In 2007, before deciding to take

on the role of the Doge, he announced his desire to sing as the baritone Simon

Boccanegra as well. So, the question on everyone’s lips is whether Domingo pulled off a

baritone role or not? (I’ll come back to this later.)

The

opera is based on true events, moreover a poem written by Lord Byron ‘The Two

Foscaris’ when Venice was going through a mercantile high; most of the gripping

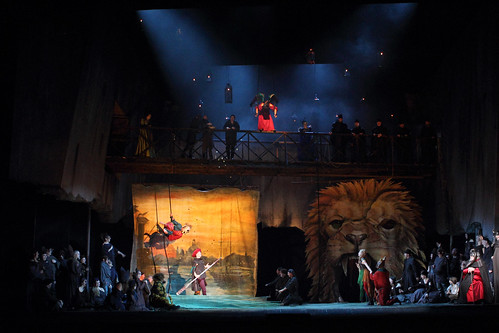

action begins before the opera has begun. In the Royal Opera House’s production

director, Thaddeus Strassberger ensures the audience is up-to-speed with italic

captions projected onto a thin screen; a screen with video projections depicting

a green murky sea representing the depth and darkness of the Venetian waters: a

glimpse of a sinister Venice set in 1457.

As

designed by Kevin

Knight, these projections and stage sets denote the age of gloominess

where punishment was gritty, bloodier and monstrous. This wickedness is

represented through Strassberger’s use of battered and chained prisoners undergoing

physical harm and persecution: being burnt, spat on, loosing a finger, etc.

I Due Foscari is an emotional opera

that bases its sentiments on family pain and tragedy; there isn’t any hope

in sight. Verdi himself was going through his own personal trauma when his wife

and two children had died in the 1840s, roughly, the same time he was compiling

his musical score for I Due Foscari.

Parallels with his own family loss are evident in I Due Foscari where the Doge looses many sons, the last of which is

lost due to a warped and deeply corrupt justice system.

During

the interval Antonio Pappano gave glimpses into Verdi’s music discussing the

use of leitmotifs and Verdi’s decision to couple particular sounds and traits

to identify the three main characters. Throughout Pappano conducted in a way,

which conveyed his surging and imminent passion for the piece. From the moment

the overture begun, until the very end, Pappano persuaded the orchestra to play

notes with might and boldness and they managed to relish and hug Verdi’s

signature melodies delicately, instilling the betrayal, darkness and lingering

emptiness shown on the bleak and torturous-looking stage. The strings, violas and

cellos bring life and sensitivity to our family opera; yet this isn’t the type

of family opera you’d want to invite your children to see.

On the contrary, the

opening carnival scene in Act 3, which include fire-eaters and contortionists

felt a little out of place. We know Venice for being inventive with their

February Carnivale, yet this was a carnival scene that seemed to have gone

wrong. The thrill of a fun and social event was bundled up against a pitch-black

stage with the sadness and eerie prison scenes from the main storyline milling in

the audiences’ head; it was difficult to appreciate these scenes, entirely.

Domingo

himself was a wonder to watch. You can only view him by also remembering that

he is a legendary opera figure and his scarlet robes with red diamonds to

frame his head only enhanced this. Often I have noticed that Domingo’s eyes

water when he sings, which, I sense, is something he naturally does when he

takes on roles that require heart wrenching and passionate arias. His ability

to show a remorseful father was unbeatable. Domingo also being a father can

empathise on many levels with the feelings of the Doge (I am sure.) Yet, his

voice was still light and far from the baritone timbre expected for the Foscari

role.

In an interview with Hugh Canning in 2010 he said, “I don’t pretend to be a baritone. But

I always like to sing roles with different colouring” and this is something we may consider as:

(a)

He wants to create his own version of Foscari in Verdi’s opera (and perhaps

other baritone roles he decides to sing) or;

(b)

He admits he is not a baritone and is aware that what he is doing may offend many, but

wants to fulfil a life goal by singing baritone roles, of his choosing, irrespectively.

The

problem lies in fact that roles are laid out with designated vocal ability. If

we start making exceptions for world-leading figures now, where do we draw the

line should other singers want to do the same and do an unsuccessful job of

it? It may upset and cause controversy

with baritone singers yet somehow Domingo has managed to get away with singing

baritone roles. From the way I see it, Domingo isn’t a baritone singer (which

he acknowledges) yet sings roles in a different voice that makes it uniquely his own version of a role. It may seem like I am letting him off, but I was convinced of his

performance as the Doge that he had the heart and zeal of a sentimental

father.

As

Foscari, in his own terms, he was refined, depressed and lonely as a father; yet this portrayal doesn’t require a baritone voice. As far as the opera is concerned however,

perhaps, Verdi wanted Foscari to be sung as a baritone to carry the vocal

traits of an authoritarian and representation of justice and law. In which

case, Domingo’s tenor and non-existent baritone voice made his Daddy Foscari character more visible than his status as the Dodge as Domingo says, [he] ‘wears the mask of

the Doge a father’s heart beats within.’Domingo, at 73, has no plans for

retiring because, as he said in a recent interview, “I can still sing".

Jacopo

Foscari sung by Francesco Meli is another story. Jacopo’s qualities as an

innocent, and handsome, son and husband are finely crafted to Meli’s mellifluous and semi-angelic

voice. Despite having to sing in a cage

or in handcuffs, he seemed to have harnessed this discomfort well for we, the

audience, didn’t hear a vocal note of anguish besides his character’s final judgment:

accused of treason by the Council of Ten.

Maria

Agresta was very strong. In the first two acts of the opera, she is the most

consistent and tenacious as the wife, Lucrezia who tirelessly begs for a pardon

for her husband’s offence, which she never gets. Her voice never faltered and

in some moments sparked a teardrop in my eye.

Evil Loredan sung by the bass singer Maurizio Muraro

should also be credited for giving a hellish performance. I’d like to see him

as commendatore in Don Giovanni one day soon, please.

The

best scene however, goes to the very end where I found Domingo at his best.

Forced out of his top position after the death of his son, underpinning the opera’s

tragedy, Placido gives it all guts, tremble and glory with more tears in his

eyes as he falls on the ground. This was awkwardly, but subtly done

with Agresta shoving her son’s face under water conveying her ‘King Lear’

insanity and downfall. I am just a bit confused as to why Strassberger decided

to add this.

I

don’t consider myself a musicologist, (I stopped learning how to play the piano

at age 10), but I’d love to know how Verdi’s less-known opera is ‘structurally

flawed’ according to some critics. The music itself, in my opinion, was mesmerizing so, it's hard to understand this comment from experts. Also, to those who said that they felt that

the Strassberger’s staging was ‘static’, well, hate to be the bearer of bad

news but from a cinematic perspective, the movement of the cameras ensured we

saw different angles; there was a great deal of action so, I’m glad I settled for the

cinema viewing.

#ROHFoscari complete turn around at last scene from @PlacidoDomingo . Heart-felt, passionate and tragic.Chorus, #Agresta #Muraro full power!

— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) October 27, 2014

Last showing is Sunday 2nd November: Click here for more information.

(Photos courtesy of the Royal Opera House. I purchased my own ticket for the HD Live screening)

%2Band%2BBeverley%2BKnight%2B(Felicia%2BFarrell).%2BPhoto%2Bcredit%2BJohan%2BPersson.jpg)

%2Band%2BKillian%2BDonnelly%2B(Huey%2BCalhoun).%2BPhoto%2Bcredit%2BJohan%2BPersson.jpg)