Showing posts with label verdi. Show all posts

Showing posts with label verdi. Show all posts

Friday, 26 August 2016

#edfringe2016: Opera Bohemia - La Traviata ★★★★★

La Traviata is Opera Bohemia’s seventh production and for the first time they are performing a work by Verdi. The independent opera company has been touring around Scotland ever since July and last night they performed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in St Cuthbert’s Church.

There’s no denying the vitality of music in La Traviata – based on the story that has inspired films including Pretty Woman and Moulin Rouge - which explains why the venue had packed out. Music Director Alistair Diggs has a way of conducting, which is almost like a performance in itself. He gave clear instructions where the ensemble of musicians followed, giving a refined performance and gravitating the music towards a more poetic and highly structured tone. The pace was neither fussy or rushed.

Catriona Clark is a starry diva as Violetta - the courtesan who dies of consumption. Clark is a vocal lecturer and consultant, outside of her opera singing, which speaks volumes about her own abilities, which is supremely impressive. Her ability to move up and down scales with little effort, or at least what seems like little effort, is astounding. Her performance of sempre libera was thrilling and had audiences gleefully bouncing to and fro in their seats. She also engages with the text and presents an excellent understanding of Violetta's disposition, making her performance a memorable one I'd happily see again.

Together with Alfredo, performed by Thomas Kinch, they convince the audience of a true romance. His characterisation is confident and fresh, and he sings with clear Italian and warmth to suit. Aaron McAuley as Giorgio Germont combines all those anti-hero characteristics one would expect from a selfish father. Yet McAuley pays special attention to Germont’s better qualities in the last few acts. His voice is also rich and his duets with Clark in act II are pivotal.

This La Traviata sparkles with great voices, sentimentality, and thoughtfulness. Even the detailed staging by Director Doughlas Nairne, is carefully managed, which changes in each act. It seems as if Opera Bohemia has covered every corner of their production, and what was performed in a small church seems as rich as an opera staged in a grand opera house.

Wednesday, 6 July 2016

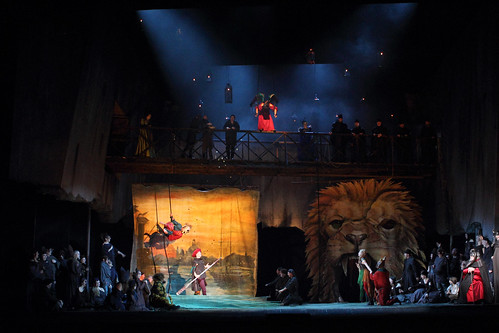

ROH: Il trovatore ★★★★

|

| Left to Right: Christopher Maltman (Count di Luna), Anna Pirozzi (Leonora), Conductor Gianandrea Noseda, Gregory Kunde (Manrico) and Marina Prudenskaya (Azucena). |

|

| Lead cast with Maurizio Muraro (Ferrando), Lauren Fagan (Ines), and David Junghoon Kim (Ruiz). |

|

| View from the box. |

The glowing music and brilliant vocal talents of the production's cast is a marvel in itself. Naples-born soprano Anna Pirozzi - certainly - brings the house down for instilling a tenacious Leonora with impressive top notes and vocal skill. Marina Prudenskaya also makes her Royal Opera House debut as the relentless Azucena. She’s the tour de force in this staging and presents a deeply tainted mother, tarnished by the child and mother she's lost.

American tenor Gregory Kunde also charms the audience with a moving rendition of 'Di quella pira', which is a reminder of how difficult Verdi made the role of Manrico. And baritone Christopher Maltman returns to the Royal Opera House singing ‘Il balen del suo sorriso’ beautifully as the Count di Luna.

Bösch’s red-hot production, however, is slightly troubled by its drab staging. The production is saved by Verdi’s music and a great cast of performers, yet the visual projections, coordinated by video designer Patrick Bannwart, are weak links. Animated butterflies fly on to the stage screen, during various scene changes, without any meaning, and it felt as if no visual life was offered elsewhere. Yet an army tank and a heart made out of barb wire and sticks, burning at the most crucial moment of the entire opera, are some of the production's saving graces.

It is Verdi’s music that will make one go and see this opera, and nothing else. For any first-timer to Il trovatore, this opera is a pleasure to watch, which Covent Garden frames as a musical triumphant. My feelings for the opera are renewed - from a Verdi opera I haven't heard of before to an opera I've learnt to cherish.

There are two casts for this production, so please check the website for further details here.

Showing until July 17th.

Anna Pirozzi deserves all the flowers and praise for instilling a tenacious Leonora. Brava! #ROHTrovatore pic.twitter.com/yjiiRxgOln— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) July 4, 2016

Completely spent! Marina Prudenskaya is a tour de force as Azucena. Powerful performance! #ROHTrovatore pic.twitter.com/p0xiY9IQLw— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) July 4, 2016

Enjoyed Manrico performed by Gregory Kunde.His Di quella pira in Act 3 is moving. SOLID vocals #ROHTrovatore pic.twitter.com/9hcy7lhwhQ— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) July 4, 2016

Christopher Maltman on great form singing beautifully Il balen del suo sorriso, as Count di Luna #ROHTrovatore pic.twitter.com/J0iqkBSBdO— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) July 4, 2016

Tuesday, 15 March 2016

Fulham Opera: Verdi's Simon Boccanegra ★★★★

It was only until the second half of the

20th century that Verdi's opera, Simon Boccanegra (1881) became recognised. It

wasn't received well during Verdi's life, with its deep reflection of the

composer's political thoughts on how Italy should be governed. His opera - on

the beleaguered Dodge who is reunited with his illegitimate daughter he thought

was dead - is currently showing at St John's Church by Fulham Opera, which

produces some of the most magical moments I've ever seen on the opera fringe

scene through its excellent cast of soloists, brave chorus and devoted

musicians.

|

| Photograph by Matthew Coughlan |

It's a shame that Simon Boccanegra isn't

performed enough, given Verdi's splendid and individual score, as well as the

versatile storyline that combines family relationships with moral redemption

and political power. Fulham Opera goes full steam on passion and shows the

audience what they have been truly missing!

Director, Fiona Williams has the audience

sitting at four corners, with the stage right in front of them. It's a clever

way to see the multiple sides of the opera's characters; some with moral

intentions while others hypocritical and motivated by wicked plans.

|

| Photograph by Matthew Coughlan |

Benjamin Woodward has the 12-piece

orchestra of Fulham Opera playing dramatically, emphasising the elegiac mood

and bitter tensions which brew during and, most of all, at the end, leading to

the Dodge's assassination by poison. The excellent chorus (Roberto Abate,

Patrizia Dina, Greg Hill, Ken Lewis, Hannah Macaulay, Rosalind O'Dowd, Naomi

Quant, Chris Childs Santos, Lilly Scott and Timothy Tompkins) take no shortcuts

and go above and beyond, singing brightly and building on the moody atmosphere;

filled with fear, uncertainty and mysticism.

With a simple stage, yet a dynamic space

for the cast, Andy Bird's coordination of changeable lights plays an important

part in marking out the intensity and symbolism for the various scene changes; moving onto a cool blue-lit night, a warm spring-like romance to a daring

red for the scheming and plotting.

|

| Photograph by Matthew Coughlan |

One thing that is wonderfully conveyed is

the relationship between Boccanegra and his daughter, Amelia, which is

masterfully executed by Emily Blanch and Oliver Gibbs. There's a little sigh of

relief when father and daughter meet again, after twenty-five years of

separation, and a few tears are shed as Amelia embraces her dying father.

Baritone lead, Gibbs plays the role of

Boccanegra who gives an unflagging and uncompromising performance as both

political leader and loving father. Blanch is charming throughout and conveys

to the audience Amelia's good nature and character, which is sustained by her

incredible and intense soprano voice.

|

| Photograph by Matthew Coughlan |

Alberto Sousa as Gabriele Adorno is simply

outstanding and reenacts the tension, anguish and complexity of Adorno's

character, dealing with love for Amelia yet lacking the knowledge that her

father is the man he has been plotting to kill. Much credit goes to Sousa for

singing exceptionally, especially for a role that many tenors turn down due to

the vocal demands.

Simon Hannigan as Jacopo Fiesco is serious,

driven and lyrical in tone whilst James Harrison plays evil-deeds Paolo Albiani

who conjures a scary and menacing conspirator with a robust baritone voice.

By the end of the first act, I was blown

away, particularly with the versatile music, high drama and heartbreaking

storyline. Fulham Opera has converted me to love an opera - that is Simon

Boccanegra. Honestly, it will leave you in awe! If there were anything to

criticise, however, it would probably be the lack of softness of the pillows

the audience had to sit on. Still it just goes to show how good the performance

was if we, the audience, were willing to endure the stiffness of our seat.

|

| Photograph by Matthew Coughlan |

Fulham Opera's Simon Boccanegra production's remaining shows are on the 18th and 20th March. Click here for more information and to purchase tickets.

Viva Boccannegra! Still in awe of tonight's performance from all -musicians and soloists. Bravo! @FulhamOpera pic.twitter.com/RPqVkzc8wL— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) March 11, 2016

★★★★ Review of Il trittico at the Royal Opera House (click here) The show ended on the 15th March 2016

★★★★ Review of Norma at the English National Opera (Click here)

★★★★ Review of Unexpected Opera's The Rinse Cycle (Click here)

Review of

Friday, 31 October 2014

ROH: Verdi's I Due Foscari with Plácido Domingo vocal 'colouring' ★★★★

By Mary Grace Nguyen

I Due Foscari is one of those opera

that isn’t performed often enough. Having seen it at the live relay in the

cinema [27th October 2014], nicely hosted by Stephen Fry, I managed

to learn more about Verdi’s earlier opera and unexpectedly enjoy it at the same

time. I disregarding what online reviews had said about the production.

It

was performed twenty years ago in Covent Garden and in 2012 the Los

Angeles Opera presented a newer production with Plácido

Domingo,

the company's general

director, to

sing the role of the baritone Doge of I Due Foscari. Yet, we know Domingo as a world

leading tenor from as far back as his opera career begun. In the 60s, he

auditioned for a baritone role in Mexico National Opera but was requested to read arias and lines in a

tenor range, which stayed with him ever since. In 2007, before deciding to take

on the role of the Doge, he announced his desire to sing as the baritone Simon

Boccanegra as well. So, the question on everyone’s lips is whether Domingo pulled off a

baritone role or not? (I’ll come back to this later.)

The

opera is based on true events, moreover a poem written by Lord Byron ‘The Two

Foscaris’ when Venice was going through a mercantile high; most of the gripping

action begins before the opera has begun. In the Royal Opera House’s production

director, Thaddeus Strassberger ensures the audience is up-to-speed with italic

captions projected onto a thin screen; a screen with video projections depicting

a green murky sea representing the depth and darkness of the Venetian waters: a

glimpse of a sinister Venice set in 1457.

As

designed by Kevin

Knight, these projections and stage sets denote the age of gloominess

where punishment was gritty, bloodier and monstrous. This wickedness is

represented through Strassberger’s use of battered and chained prisoners undergoing

physical harm and persecution: being burnt, spat on, loosing a finger, etc.

I Due Foscari is an emotional opera

that bases its sentiments on family pain and tragedy; there isn’t any hope

in sight. Verdi himself was going through his own personal trauma when his wife

and two children had died in the 1840s, roughly, the same time he was compiling

his musical score for I Due Foscari.

Parallels with his own family loss are evident in I Due Foscari where the Doge looses many sons, the last of which is

lost due to a warped and deeply corrupt justice system.

During

the interval Antonio Pappano gave glimpses into Verdi’s music discussing the

use of leitmotifs and Verdi’s decision to couple particular sounds and traits

to identify the three main characters. Throughout Pappano conducted in a way,

which conveyed his surging and imminent passion for the piece. From the moment

the overture begun, until the very end, Pappano persuaded the orchestra to play

notes with might and boldness and they managed to relish and hug Verdi’s

signature melodies delicately, instilling the betrayal, darkness and lingering

emptiness shown on the bleak and torturous-looking stage. The strings, violas and

cellos bring life and sensitivity to our family opera; yet this isn’t the type

of family opera you’d want to invite your children to see.

On the contrary, the

opening carnival scene in Act 3, which include fire-eaters and contortionists

felt a little out of place. We know Venice for being inventive with their

February Carnivale, yet this was a carnival scene that seemed to have gone

wrong. The thrill of a fun and social event was bundled up against a pitch-black

stage with the sadness and eerie prison scenes from the main storyline milling in

the audiences’ head; it was difficult to appreciate these scenes, entirely.

Domingo

himself was a wonder to watch. You can only view him by also remembering that

he is a legendary opera figure and his scarlet robes with red diamonds to

frame his head only enhanced this. Often I have noticed that Domingo’s eyes

water when he sings, which, I sense, is something he naturally does when he

takes on roles that require heart wrenching and passionate arias. His ability

to show a remorseful father was unbeatable. Domingo also being a father can

empathise on many levels with the feelings of the Doge (I am sure.) Yet, his

voice was still light and far from the baritone timbre expected for the Foscari

role.

In an interview with Hugh Canning in 2010 he said, “I don’t pretend to be a baritone. But

I always like to sing roles with different colouring” and this is something we may consider as:

(a)

He wants to create his own version of Foscari in Verdi’s opera (and perhaps

other baritone roles he decides to sing) or;

(b)

He admits he is not a baritone and is aware that what he is doing may offend many, but

wants to fulfil a life goal by singing baritone roles, of his choosing, irrespectively.

The

problem lies in fact that roles are laid out with designated vocal ability. If

we start making exceptions for world-leading figures now, where do we draw the

line should other singers want to do the same and do an unsuccessful job of

it? It may upset and cause controversy

with baritone singers yet somehow Domingo has managed to get away with singing

baritone roles. From the way I see it, Domingo isn’t a baritone singer (which

he acknowledges) yet sings roles in a different voice that makes it uniquely his own version of a role. It may seem like I am letting him off, but I was convinced of his

performance as the Doge that he had the heart and zeal of a sentimental

father.

As

Foscari, in his own terms, he was refined, depressed and lonely as a father; yet this portrayal doesn’t require a baritone voice. As far as the opera is concerned however,

perhaps, Verdi wanted Foscari to be sung as a baritone to carry the vocal

traits of an authoritarian and representation of justice and law. In which

case, Domingo’s tenor and non-existent baritone voice made his Daddy Foscari character more visible than his status as the Dodge as Domingo says, [he] ‘wears the mask of

the Doge a father’s heart beats within.’Domingo, at 73, has no plans for

retiring because, as he said in a recent interview, “I can still sing".

Jacopo

Foscari sung by Francesco Meli is another story. Jacopo’s qualities as an

innocent, and handsome, son and husband are finely crafted to Meli’s mellifluous and semi-angelic

voice. Despite having to sing in a cage

or in handcuffs, he seemed to have harnessed this discomfort well for we, the

audience, didn’t hear a vocal note of anguish besides his character’s final judgment:

accused of treason by the Council of Ten.

Maria

Agresta was very strong. In the first two acts of the opera, she is the most

consistent and tenacious as the wife, Lucrezia who tirelessly begs for a pardon

for her husband’s offence, which she never gets. Her voice never faltered and

in some moments sparked a teardrop in my eye.

Evil Loredan sung by the bass singer Maurizio Muraro

should also be credited for giving a hellish performance. I’d like to see him

as commendatore in Don Giovanni one day soon, please.

The

best scene however, goes to the very end where I found Domingo at his best.

Forced out of his top position after the death of his son, underpinning the opera’s

tragedy, Placido gives it all guts, tremble and glory with more tears in his

eyes as he falls on the ground. This was awkwardly, but subtly done

with Agresta shoving her son’s face under water conveying her ‘King Lear’

insanity and downfall. I am just a bit confused as to why Strassberger decided

to add this.

I

don’t consider myself a musicologist, (I stopped learning how to play the piano

at age 10), but I’d love to know how Verdi’s less-known opera is ‘structurally

flawed’ according to some critics. The music itself, in my opinion, was mesmerizing so, it's hard to understand this comment from experts. Also, to those who said that they felt that

the Strassberger’s staging was ‘static’, well, hate to be the bearer of bad

news but from a cinematic perspective, the movement of the cameras ensured we

saw different angles; there was a great deal of action so, I’m glad I settled for the

cinema viewing.

#ROHFoscari complete turn around at last scene from @PlacidoDomingo . Heart-felt, passionate and tragic.Chorus, #Agresta #Muraro full power!

— Mary Grace Nguyen (@MaryGNguyen) October 27, 2014

Last showing is Sunday 2nd November: Click here for more information.

(Photos courtesy of the Royal Opera House. I purchased my own ticket for the HD Live screening)

Saturday, 27 September 2014

ENO : Otello - I cannot question Verdi's highly developed orchestral work ★★★

Verdi visited England in 1847 when he first saw Shakespeare’s Othello. This moved him and the librettist

Arrigo Boïto to complete their own opera of the play in 1887. It is claimed to be Verdi’s 'most highly developed orchestral work' and David Alden’s production doesn't leave this fact out.

Currently showing at the ENO, Alden’s production encapsulates Verdi’s musical sophistication, courtesy of ENO musical director Edward Gardener and the ENO orchestra, and the dramatic mastery of Shakespeare’s tragic and deceitful tale. Yet despite the vocal strength of its cast members and empowering orchestral beauty, I found that, the production was difficult to follow as the stage was half-baked and filled with underdeveloped characters.

Currently showing at the ENO, Alden’s production encapsulates Verdi’s musical sophistication, courtesy of ENO musical director Edward Gardener and the ENO orchestra, and the dramatic mastery of Shakespeare’s tragic and deceitful tale. Yet despite the vocal strength of its cast members and empowering orchestral beauty, I found that, the production was difficult to follow as the stage was half-baked and filled with underdeveloped characters.

Set in a Cypriot 19th

century church with unelaborate period

costumes and minimalistic staging, lights, directed by Adam Silverman,

play a huge part in demystifying the

grit and greed of Iago, which is sung by Jonathan Summers. This is contrasted with the white dressed and

pure Roderigo (Peter Van Hulle) and Desdemona sung by American Soprano

Leah Crocetto.

Boïto originally insisted the opera be named Iago, not only because Rossini had

already written his own opera but, due to its sole focus; it's based on the hypocritical villain and not the moor. Boïto cut out the first act to get

straight into the tumult of psychological manipulation and Otello’s downfall.

This adds nicely to the production’s lack of controversy over a blackened-face Othello, which is, often, depicted in opera and theatre. Aleksandrs Antonenko had to endure the brute of a face painted Otello in the Royal Opera

House in 2012.

Stuart Skelton, Male Singer of the Year at the International Opera

Awards and winner of Olivier Award as Peter Grimes, sung as a gutsy and

glorified Otello. He ignites an Otello obsessed with the idea of being loved by

Desdemona and easily swayed and sickened by his own deluded insecurity which is perpetuated

by Iago.

Yet Summers, as Otello’s chief lieutenant, doesn’t show a shed of evil from the

get-go; in fact he shows a deadened and emotionless Iago that, although, sings

of his desire and plans to rid him of his ‘lackey’ status, illustrates an absence of passion. It is only when he sits at

the edge of the stage and narrates to the audience in a sung soliloquy ‘there is nothing, heaven is a lie’ , just before the interval, that we sense his malevolent yearning. It is hard to pin down Summer’s Iago as he moves from one extreme to

another; a nihilist one moment to subtle

acts of homoeroticism, which cushion Otello’s paranoia and emasculating

features.

The last few scenes are powerful. We watch Desdemona prepare for her

death and this is where Crocetto is at her

best. She envisages Verdi's victimised Desdemona that we, opera-goers, want to see. Crocetto’s

cor anglais solo and ‘willow song’

brought, some, tears to the audience’s eyes which is culminated with

the silence

of the orchestra as she wails loudly of her injustice to Emilia

(Pamela Helen Stephen.)

Unfortunately, although both vocally tenacious,

I felt that, Crocetto and Skelton were individually

stronger when they sung their own arias than when they sung as a couple. For me, their grand duet was

devoid of affection and passion (and I wasn't entirely unconvinced of their acting together despite

how much they embraced each other.) This is a significant part of the opera as it highlights the deeper tragedy that leads to Desdemona's unfair death, which - sadly- the production failed to bring out.

The ending is dramatic and saddened by the looming Iago that stays alive

and unpunished at the corner of the stage. In true

operatic style, justice is not served and, in the same way, the production did not

give Otello the full breathe and life it

deserved.

Besides my dissatisfaction with characterisation there were some stage directions that I thought needed tweaking, as well. For example, in Act II when ENO chorus singers sung “wherever you look, brightness

shines..." Desdemona watches the children dance, yet the chorus

singers' voices were far and hidden from the stage that the audience

could

hear the tapping of shoes when it should have been the other way

round. Come on ENO, what's going on?

I cannot question the orchestra, the voices (Crocetto, Summers, Skelton, Van Hulle and Helen Stephen), or the music behind it all; but I would be lying if I said I wasn't slightly disappointed of the production as a whole.

Monday, 19 May 2014

Think you know enough about Verdi's 'La Traviata' in time for the Royal Opera House's #BPbigscreens? Think again.

Context notes and Synopsis

I have included details on:

- Verdi's inspirations

- Violetta's characterisation

- Short section on the music

- Modern films inspired by the opera

- Clips from other presentations of the opera

- Why it is regarded as No.1 in the world according to Operabase.com.

There should be enough information to get

you in the mood for the Royal Opera House's #BPbigscreens of 'La Traviata' taking place

on 20th May. (All views are my own.)

More literature about the cast and the production: Click here

(This is the version to be shown on the 20th May)

Context

(This is the version to be shown on the 20th May)

Context

On 2nd

February 1852 Verdi saw Alexandre Dumas’ play, ‘La Dame aux caméllias’ in Paris,

which was the inspiration behind 'La Traviata.' ‘La Dame aux

caméllias’

is based on

Damas’ own novel about Marie Duplessis (1824-47); he dubs her as

Marguerite Gautier in the play. Dumas bases the story on his true account of

the relationship he had with Marie who suffered consequences such as Marie’s

infidelity in addition to financial difficulties which is unlike 'La Traviata'

which

uses a father figure to break the relationship. Marie was characterised as a

Parisian courtesan with wit and beauty who carried a bouquet of camellias and

died of consumption at the age of 23. Dumas depicts her as a part of the

demimonde whose lifestyle choices and immorality offended the puritan values of

the 19th century.

Some historians have suggested that

Verdi’s interest in ‘La Dame aux

caméllias’ can be seen through his own

personal life, which may have added to his aspirations in creating 'La

Traviata.' This involved his love affair with Giuseppina Streppon, who had two

illegitimate children, which

generated considerable scandal among the citizens

of Busetto

and

his father figure, Antonio Barezzi, who criticised him for continuing the

relationship.

Francesco Maria Piave was the

librettist for 'La Traviata' who managed to write a first draft within five

days, reducing

the five acts from Dumas’ play into three. It focuses on

three main characters: Violetta, Alfredo and Germont.

On the premiére

of 'La Traviata' at La Fenice in Venice on 6 March 1853, the performance was

described as a disaster and Verdi even wrote to his friend Tito Ricordi,

‘Unfortunately, I have to send you sad news, but I can’t conceal the truth from

you. Traviata was a fiasco. Don’t try to work out the reason, that’s just the

way it is. ‘ However, Verdi already had his concerns regarded the production.

Firstly, the lead Soprano, Salvini- Donatelli (1815 – 1891), who was not his

first choice, was 38 years old and weighed over 20 stone, which was the antithesis of

how Verdi would have wanted Violetta to be casted. His ideal Violetta would have been ‘young,

had a graceful figure and could sing with passion.’ Unfortunately, for Donatelli,

who received good reviews for her voice, was laughed at soon after Act 1 and

towards the end of the opera.

Verdi, also, sought to add a

contemporary touch to the opera and

requested the singers be

in modern dress; the opera was also regarded as being the first for dealing with such

censored and immoral topics including sexuality, prostitution and the disease:

consumption. This was not popular among various countries, so much so

that La Fenice

declined Verdi's request for contemporary costume and insisted the singers be

dressed in 17th century costume – the era of Richelieu – to keep the

opera’s provocative and highly controversial ideas at a distance. At the time, operas portraying death

through consumption were considered taboo, as it was a deadly disease that could

take life in a matter of months.

After 14 months of withdrawing the

opera, revisions and amendments were made between 1853 and May 1854 particularly

on Act 2 and Act 3. They were performed, on Verdi’s approval, at the Teatro San

Benedetto and Violetta was sung by Maria Spezia-Aldighieri who was closer to

Verdi’s ideal casting. As a result, it was a successful performance that was produced

all over Italy and Europe, always

in 18th century costume.

Violetta

Following the revival after the

Teatro San Benedetto (1854) Giulio Ricordi recommended Soprano, Gemma

Bellincioni, for the next role as Desdemona in ‘Otello’ having

been cast as

Violetta. But Verdi replied, ‘I couldn’t judge her from 'La Traviata'; even a

mediocrity could possess the right qualities to shine in that opera and be

dreadful in everything else.’ For Verdi, Violetta was a ‘near perfect union’ of

music and drama. He thought that a strong and dynamic coloratura soprano was needed to

highlight the glamour and extravagance of Violetta’s Parisian lifestyle from 'Sempre

libera’ to, then, infuse emotion, death and love together through her agility

and stamina to sing powerfully for songs such as ‘Amami, Alfredo’ without the

use of flourishes.

The

Music

Often, like other operas, 'La

Traviata' songs have be used for commercial reasons which maybe recognisable to

some, even if they have not seen the complete opera.

Rhythmic choruses of the matadors,

gypsies and carnival music are often familiar songs.

For a

love story, viewers may question

its

usage in such a heartrending opera but, in

fact, these choruses are used as dramatic device deliberately added by Verdi to

provide calm after emotional outpouring moments by Violetta in Act 1, Act 3 as

well as Act 2 where she dashes to Flora’s party leaving Alfredo behind.

When Violetta sings ‘Amami, Alfredo,’

it is the single most poignant part of the entire opera

, in my opinion (which

brings me to tears each and every time.) As much as her words ask for Alfredo’s

love in the cheerful sense, coloratura sopranos must face the challenge of

conveying a Violetta that betrays her outward appearance whilst instilling the

sadness of abandoning him and their love.

This is a clip from Willy Decker’s 2005 production at the Salzburg Festival; notice the use of a large clock as the centerpiece for the stage (by Wolfgang Gussman) to signify Violetta’s impending death. Anna Netrebko’s is Violetta, Rolando Villazón is Alfredo and Thomas Hampson as Germont. Villazón viciously stuffs and throws money all over Netrebko’s body, which although unsettling is quite effective.

Placido Domingo is Alfredo in Franco Zeffirelli film of ‘La Traviata.’ At the age of 20, Domingo made his debut in Mexico and later admitted that he, ‘had not yet learned to control his emotions.’ Teresa Stratas’ Violetta encapsulates a lot of the elements Verdi would have wanted in his ideal Violetta (in my view.) Cornell MacNeil plays Germont.

Modern

Film

Modern

Film

Gary Marshall’s 1990 romcom ‘Pretty

Woman’ is the most obvious movie that represents certain aspects of ‘La

Traviata’ given that the heroine who is an inexperienced prostitute, Vivian

Ward (Julian Roberts) falls for the handsome and successful businessman, Edward

Lewis (Richard Gere). One of Lewis’ ways of courtship includes sweeping her off

by private jet to watch ‘La Traviata’ on stage (how fitting?) She tells an

audience member, ‘Oh, it was so good, I almost peed my

pants! to ‘which Edward translates as, ‘she said she liked it better than The Pirates of Penzance.’ However,

the big difference between Ward and Violetta is that this prostitute gets her

happy ending.

Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 romance musical ‘Moulin

Rouge’ was also inspired by ‘La Traviata’ but (I believe) has more plot

elements from ‘La Dame aux

caméllias.'

Also set in Paris the

red light district of Montmartre,

a young English writer and talented musician, Christian (Ewan

McGregor) falls in love with courtesan and cabaret dancer, Satine

(Nicole

Kidman.) (Luhrmann was inspired by the Greek mythology of 'Orpheus and

Eurydice' in making Christian a musical genius.) Satine, like Violetta,

suffers from consumption and has to forfeit her

relationship with Christian to secure the rights to the Moulin Rouge,

staying

loyal to the theatre and appease its investor, the Duke of Monroth.

This is

all at the advice of Harold Zidler; the owner for the Moulin Rouge and

(in our

case,) Satine’s father figure who tells her to leave her love,

Christian, behind.

Why

is 'La Traviata' rated No. 1 by the world according to Operabase.com

‘La Traviata’ is a love tragedy that

underpins the suffering of a woman – a high-class prostitute – who is put in the

spotlight of Parisian society. Supposedly, a beautiful and witty courtesan she

is, in fact, fatally ill, and, despite being in love with a wealthy man, who

loves her back

(which is, perhaps, not

often the case) she is requested to

leave

and relinquish any hope she has of them being together. There is also

her

willingness to move to the country, sell her possessions and support

them financially, which subverts her position from prostitute to

protector. However, as we see later on, her lover turns his back on her

by

embarrassing her in front of society by throwing his winnings at her,

whereby

society and his own father, pity her and condemn the man’s behavior.

From Violetta’s coughing and

repetitive mention of her looming illness, the audience is led into an opera

focusing on the life of an immoral character; a contemporary subject that we

would not usually pity, but for Violetta, we do. This opera draws on

controversial and opposing themes at the same time, which is what makes ‘La

Traviata’ an original opera with reference to prostitution, love, social hierarchy and consumption. Looking back at how

contentiously

‘La Traviata’ was

received from

its

first showing in Venice (1953,) it is a testament

to

how these 19th

century values have left us, and to some

degree have not; no-one

no one has

created a opera about lovers torn apart by HIV, but there is 'Rent' the theatre show.

Verdi’s use of both sorrowful arias

coupled with

timed dances and carnival songs breaks

up an emotional storyline, again evoking

the use of contraries, which work remarkably well in this opera. In its entirely, with

the combination of these dramaturgical themes and literary necessities and, more

importantly, Verdi’s overwhelming rich musical score, this can only be but a

timeless and memorable opera that affects us all. It is, however, the task of

the director and production company to ensure they find the appropriate coloratura soprano to cast Violetta

just as Verdi would have so wanted.

The Synopsis

This synopsis is based on the libretto. Productions

may amend and change the opera as the director sees fit.

ACT 1

It is 1850; Violetta

Valéry

throws a party in the salon of her Paris mansion secured by the Baron Douphol, her protector. Violetta (in earlier productions) is

known for carrying a bouquet of camellias. She suffers from consumption - a

fatal respiratory disease.

Her conversation with her doctor Dr. Grenvil is interrupted as guests enter, including Flora Bervoix, another courtesan who

is financed by the Marchese; the Marquis; Gastone, a Viscount, introduces

Violetta to Alfredo Germont, a

young man from a provincial family in Provence, and tells her that Alfredo has fallen in love with her from afar

and had been enquiring about her health daily. She then decides to chide

the Baron for not being as attentive as Alfredo,

as he replies, ‘I’ve known you only a year.’

Alfredo

proposes a toast to love and pleasure, Libiamo

ne’ lieti calici, and the partygoers join in his drinking song, ‘Brindisi’;

Violetta rejoices as well and says life’s many pleasures need to be enjoyed.

She encourages her guests to go to the next room and dance to the music of an

accompaniment band, but suddenly she has a coughing fit and feels so ill that she has to sit down.

Alfredo immediately comes to her attention even though she insists that he not

worry and carry on enjoying the party, as ‘the chill will pass.’ He tells her

that he must take care of herself to which she replies that she cannot afford

to sacrifice her consumptive lifestyle. Here, Alfredo confesses that he has

secretly loved her Di quell’amor, quell’

amor ché

palpito for a year Un di felice o. At first, she questions

his sincerity with the belief that romance cannot exist for her - a woman from

the demimonde, and requests he forget her, as friendship is all she can offer

him. She then hands him a

camellia (depending on the production) and asks he return it when it has withered

which he persuades her is ‘tomorrow!’ Oh ciel! Domani Alfredo leaves and the guests and chorus and soloists take part

in a large ‘Verdi’ chorus Si ridesta in

ciel l’aurora, and exit after.

Left alone, Violetta is ecstatic of Alfredo’s love

and admits she loves him too Ah, forśè lui che l’anima soling ne’ tumulti. Yet, she

battles with her emotions, going to and fro, pondering her lavish and fashionable

courtesan lifestyle, her loneliness and unsuitability for Alfredo’s love. She asks

herself whether risking all of her extravagant privileges for his love is

worthy as she is afraid it will be painful - as she lives for pleasure Sempre libera degg’io folleggiare di gioia

in gioia. Yet, Alfredo sings from below her balcony Di quell’amor , which is an echo and reminder to Violetta of his

love, which adds to her confusion. The scene ends with a repetition of her determination

to be free and to live for the moment.

Act 2 Scene 1

Set in a country house outside of Paris, Violetta

and Alfredo have been living happily together De’ miei bollenti spiriti for 3 – 5 months (the actual duration varies between operas). Violetta has

sacrificed the Parisian city

life to be with Alfredo; however, Violetta still lives luxuriously and pays for

all their bills, which Alfredo is only made aware of by Annina, Violetta’s maid. Alfredo feels ashamed O mio rimorso! O infamia! to hear that

Violetta has requested Annina to sell off her horses, carriages and possessions

to finance their living costs. She tells him that money is running out, so he immediately heads to Paris to try and raise

more.

Violetta enters and Giuseppe, a servant, gives her

an invitation from Flora to a party taking place that evening but she puts this

aside. She welcomes in a man she thought was a financial adviser when it is,

actually, Alfredo’s father, Giorgio Germont. He is impolite towards her;

accuses her of seeking his son’s fortune and destroying his reputation, but she proves him

wrong by showing papers that she

is supporting them - and not living on Alfredo’s income. She also admits to

Giorgio that she is selling her possessions, at which point he realises he has misjudged her.

Irrespective of this, Germont requests she leaves Alfredo for the sake of his

two children, of which she has

no knowledge Di due figli, and the

sake of Alfredo’s sister whose marriage is being jeopardised by their scandalous

relationship Pura siccome un angelo.

Violetta accepts that she may have to leave Alfredo

for a while but Germont insists this must be forever. This upsets Violetta as she pleads with him not to make

her have to make such a sacrifice of letting Alfredo go; she tells him she

cannot live without Alfredo Non sapete

quale affetto vivo. Yet, Germont is unsympathetic and says their love

affair is not blessed by heaven, and that his son’s desire for her will

eventually fade Un dì, quando le veneri. Violetta gives in, weeps and decides that she will leave Alfredo

as she says to Germont, ‘tell the pure and beautiful maiden, that an

unfortunate woman, crushed by despair, sacrifices herself for her, and will

die.’ Germont pities and venerates

Violetta for her willingness to put his daughter first Piangi, Piangi, Piangi, o

misera! He asks her to tell Alfredo that she no longer loves him and she asks

him for an embrace as if she were his daughter. Germont bids her farewell and

goes out to the garden to wait for Alfredo on Violetta’s request, as she knows

that Alfredo will be distraught with the news.

When Germont leaves, Violetta mourns and accepts

Flora’s invitation to the party. (In other operas, Violetta writes a letter to

the Baron Douplol.) She begins to write a

farewell letter to Alfredo, but he interrupts her. She resists showing the

letter to him, and, at the same time, he tells her that his father will like

her. (In some versions, Alfredo is worried over a note he had received from his

father whom he is

expecting.) Violetta’s emotions are uncontrollable as she cries and bids to Alfredo

‘Love me, Alfredo. Love me as much as I love you’ Annina, Alfredo, quant’io t’amo. Here, Verdi has marked the score

with con passion e forza.

Once Violetta leaves,

Alfredo, unaware of Violetta’s endeavour to leave him, is content momentarily

until Giuseppe tells him that Violetta has left for Paris and a messenger gives

him the letter from Violetta soon after. He reads the words, ‘Alfredo, by the

time you receive this letter…’ and bursts into tears and embraces his father.

Germont consoles him and tells him to consider his life in Provence Di Provenza il mar but Alfredo ignores

him; enraged and jealous of the Baron, he sees Flora’s invitation and makes way

to the party with his father following him.

Act 2 Scene 2

Flora’s

party takes place in her salon, which the Marquis has paid for. There are

gypsies dancing to their song Noi siamo

zingarelle and some guests are dressed like matadors and picadors. The

Marquis tells Flora that Violetta and Alfredo are no longer together and that

Violetta will be coming with the Baron instead. When Alfredo enters, Flora asks

for Violetta; he says he knows nothing of her and heads to the gambling table.

Violetta and the Baron enter in together and the both see that Alfredo is

there; here, the Baron forbids her to speak to him, and Violetta, shocked that

he is there, asks God for mercy. The Baron challenges Alfredo to play for high stakes,

and Alfredo continually wins as he says, ‘Unlucky in love, lucky at cards.’ When supper is announced, all the guests go to the dining

room and the Baron discretely requests a rematch. Violetta enters after having

left a message for Alfredo to speak to her.

Alfredo

enters the scene in anger, asking why she has summoned him; she warns him that

the Baron wants to challenge him to a duel and advises him to leave. Alfredo, however, accuses her of being

selfish for thinking that if he won the duel she would lose both lover and

keeper. She tries to convince him that she is genuinely worried for his life,

and tells him that she loves the Baron. Alfredo calls all the guests and

exclaims how foolish he was in letting Violetta waste her money on him. He asks

them to bear witness to him repaying his debts to Violetta, as he sarcastically

says Qui or testimon vi chiamo

che qui pagata io l’ho and throws his winnings at her (or onto her

feet in some versions); she faints. Everyone is outraged and, at this moment,

Alfredo’s father steps in and expresses his contempt for his son’s behavior and

show of disrespect for Violetta. He says: “A man who insults a woman, even in anger, is himself worthy only of

contempt.” Even though Alfredo feels guilt and shame for what he has done,

Violetta tells him that God will forgive him and she will still love him in

death Ah! Io spenta ancora, pur t’amerò. Alfredo

is led away by his father, and the Baron challenges him to a duel. The act ends

with another Verdi chorus expressing the remorse and sympathy felt for

Violetta’s suffering.

Act 3

The following month, Violetta is in her bedroom laying on her deathbed

in critical condition. She is penniless and attended by Annina only. (Several

versions include a priest and the doctor present who tells Annina that Violetta

has only a few hours to live.) Violetta instructs Annina to give half of the

money remaining to the poor and when Annina leaves, she begins to read (not

sing) a letter from Germont describing Alfredo being abroad after having

wounded the Baron and shall return to seek her forgiveness. But, it is too late

È tardi! , as she knows that her

health is deteriorating and she will die at any moment as she sings - as a

fallen woman - farewell to all her happy dreams Ah, della traviata sorridi al desìo. A carnival baccanale

takes place outside to signify her impending death.

Annina

returns with exciting news that Alfredo has been seen and is making his way to

her, and he makes a big entrance; he runs to her and they embrace in each

other’s arms. He promises to take her to Paris so they can be together and she

can recover Parigi, o cara, noi

lasceremo. Violetta is so filled with happiness and energy that she begins

to prepare to go to church to thank God for Alfredo’s return; yet this is only momentary,

as she faints. Here, Alfredo realises the severity of her illness and Violetta

is desperate to be with Alfredo Ah, Gran

Dio! Morir sì giovane.

Germont

(accompanied by the doctor in some operas) enters and embraces Violetta as he

had once promised to her before. Violetta gives Alfredo a locket (or medallion

in some versions) with a portrait of herself and tells him, ‘If some pure-hearted girl in the flower of her youth

should give you her heart, let her be your wife. It’s what I’d want.’ Alfredo is miserable and cannot accept what

is happening No, non morrai, non dirmelo.

She tells him to deliver the message that an angel in heaven is

praying over them. Suddenly, Violetta begins to feel rejuvenated and rises to

her feet in joy Oh gioia and then

dies.

References: Great Operas, Michael Steen (2012)

The Complete Operas of Verdi, Charles Osborne (1997)

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Opera, Stanley Sadie (2004)

The Operas of Verdi: Volume 2, Julian Budden (1992)

La traviata Opera Guide Roger Parker, Anna Picard, et al. (2013)

La traviata Opera Guide, Nicholas John, Denis Arnold, et al. (1985)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

%20Alastair%20Muir.jpg)